In a way, some of the first aviators were also the last Romantic adventurers.

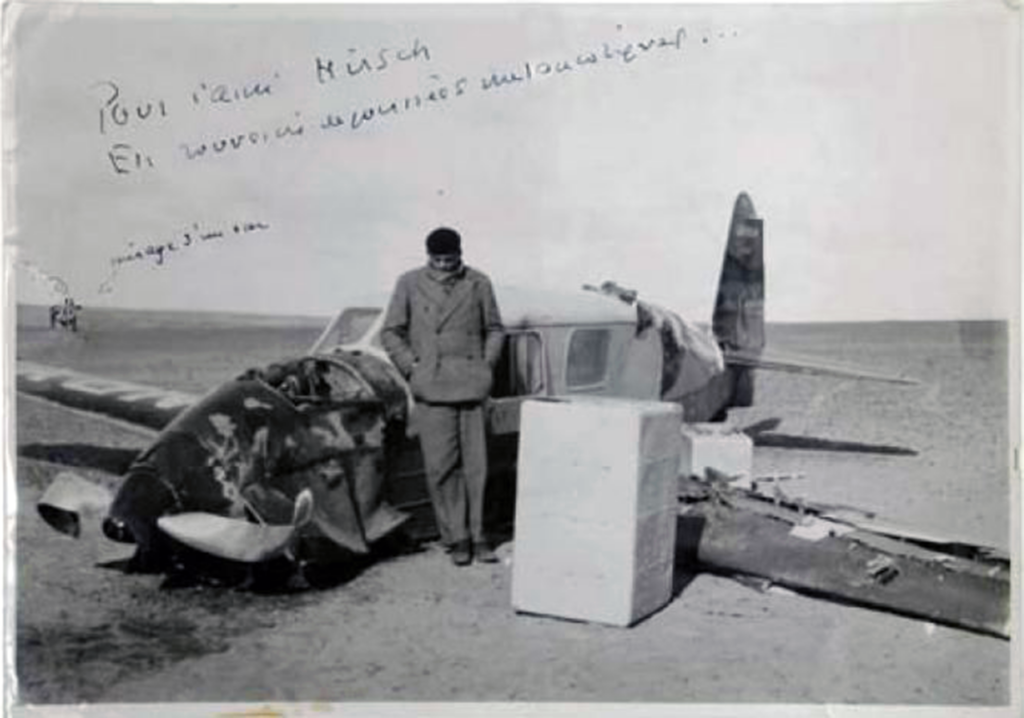

Consider Antoine de Saint-Exupéry, the aviator-author. In his life, he weaved the intensity of the human spirit intertwined with action, intuition, and experience.

To Saint-Exupéry, design was a necessity and, hence, it had a utilitarian goal; but great designs were much more than utility since they were easy to use and, above all, ˝meaningful.˝

Overall, Saint-Exupéry shows that art, design, and the human spirit are all facets of the same drive: to create, overcome, and forge connections in a world that seemed to accelerate and lose its meaning at times. He found beauty in experience —and the importance of human connection forged through shared challenges.

˝In anything at all, perfection is finally attained not when there is no longer anything to add, but when there is no longer anything to take away, when a body has been stripped down to its nakedness.˝

Antoine de Saint-Exupéry, Wind, Sand and Stars (Terre des hommes, 1939).

At Biokabin, we work so that what we learned with our reads, experience, and prototypes create a dwelling that isn’t only memorable and packed with utility, but healthy and ˝meaningful.˝

A bit of context follows regarding this quote by Antoine de Saint-Exuppéry apropos of tools, design, simplicity and repeated processes that, despite being industrial, maintain its craftsmanship spirit. Here’s Saint-Exupéry reflecting on an airplane’s fuselage in the 1930s (Chapter III, The Tool).

Here’s the whole excerpt:

˝It is as if there were a natural law which ordained that to achieve this end, to refine the curve of a piece of furniture, or a ship’s keel, or the fuselage of an airplane, until gradually it partakes of the elementary purity of the curve of a human breast or shoulder, there must be the experimentation of several generations of craftsmen.

˝In anything at all, perfection is finally attained not when there is no longer anything to add, but when there is no longer anything to take away, when a body has been stripped down to its nakedness.

˝It results from this that perfection of invention touches hands with absence of invention, as if that line which the human eye will follow with effortless delight were a line that had not been invented but simply discovered, had in the beginning been hidden by nature and in the end been found by the engineer. There is an ancient myth about the image asleep in the block of marble until it is carefully disengaged by the sculptor. The sculptor must himself feel that he is not so much inventing or shaping the curve of breast or shoulder as delivering the image from its prison.

˝In this spirit do engineers, physicists concerned with thermodynamics, and the swarm of preoccupied draughtsmen tackle their work. In appearance, but only on appearance, they seem to be polishing surfaces and refining away angles, easing this joint or stabilizing that wing, rendering these parts invisible, so that in the end there is no longer a wing hooked to a framework but a form flawless in its perfection, completely disengaged from its matrix, a sort of spontaneous whole, its parts mysteriously fused together and resembling in their unity a poem.˝

Antoine de Saint-Exupéry, Wind, Sand and Stars (Terre des hommes, 1939).

And here’s the original text (in French) by Antoine de Saint-Exupéry

« Notre maison se fera sans doute, peu à peu, plus humaine. La machine elle-même, plus elle se perfectionne, plus elle s’efface derrière son rôle. Il semble que tout l’effort industriel de l’homme, tous ses calculs, toutes ses nuits de veille sur les épures, n’aboutissent, comme signes visibles, qu’à la seule simplicité, comme s’il fallait l’expérience de plusieurs générations pour dégager peu à peu la courbe d’une colonne, d’une carène, ou d’un fuselage d’avion, jusqu’à leur rendre la pureté élémentaire de la courbe d’un sein ou d’une épaule.

« Il semble que le travail des ingénieurs, des dessinateurs, des calculateurs du bureau d’études ne soit ainsi en apparence, que de polir et d’effacer, d’alléger ce raccord, d’équilibrer cette aile, jusqu’à ce qu’on ne la remarque plus, jusqu’à ce qu’il n’y ait plus une aile accrochée à un fuselage, mais une forme parfaitement épanouie, enfin dégagée de sa gangue, une sorte d’ensemble spontané, mystérieusement lié, et de la même qualité que celle du poème.

« Il semble que la perfection soit atteinte non quand il n’y a plus rien à ajouter, mais quand il n’y a plus rien à retrancher. Au terme de son évolution, la machine se dissimule. La perfection de l’invention confine ainsi à l’absence d’invention. Et, de même que, dans l’instrument, toute mécanique apparente s’est peu à peu effacée, et qu’il nous est livré un objet aussi naturel qu’un galet poli par la mer, il est également admirable que, dans son usage même, la machine peu à peu se fasse oublier.

« Nous étions autrefois en contact avec une usine compliquée. Mais aujourd’hui nous oublions qu’un moteur tourne. Il répond enfin à sa fonction, qui est de tourner, comme un cœur bat, et nous ne prêtons point, non plus, attention à notre cœur. Cette attention n’est plus absorbée par l’outil. Au-delà de l’outil, et à travers lui, c’est la vieille nature que nous retrouvons, celle du jardinier, du navigateur, ou du poète. »

Antoine de Saint-Exupéry, Wind, Sand and Stars (Terre des hommes, 1939).